Alcohol misuse can lead to alcohol-associated hepatitis (AH), a form of liver disease with a high short-term mortality rate in severe cases. Currently, no medications have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat AH, and liver transplantation is often required due to liver failure. A better understanding of how AH develops could help improve AH treatment and prevent progression to severe disease. A recent study has shown a positive correlation among neutrophilic infiltration and the model for end-stage liver disease score (MELD score, a scoring system predicting prognosis of liver disease) and serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels. Researchers found a mechanism by which neutrophils—a type of white blood cell—contribute to liver injury in AH. Published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, the study was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

A growing body of evidence indicates that various types of cells in the body’s immune system are involved in AH, including neutrophils. When a person develops severe AH, the levels of neutrophils increase in the liver, but how these cells contribute to the development of the disease is not clear. To gain insight, the researchers examined neutrophils and other immune cells in the livers of 40 patients with severe AH. The authors showed that neutrophil-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS) promoted liver injury and inflammation in the experimental model. This suggests that neutrophil-generated ROS is one of the mechanisms that contribute to liver injury and dysfunction in severe AH in addition to many other cell types involved in severe AH pathogenesis.

More specifically, the researchers found increased expression of neutrophil cytosolic factor 1 (NCF1), a gene involved in controlling ROS. To gain insight into the mechanism of NCF1 in severe AH with high neutrophil levels, the researchers examined NCF1 in an animal model of liver injury. They found that NCF1 contributes to higher levels of ROS and thus liver inflammation/injury by inhibiting adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK, a key regulator of lipid metabolism) and by inhibiting microRNA-223 (a key anti-inflammatory microRNA). MicroRNAs are non-coding RNA molecules thought to play a key role in the regulation of gene expression.

These findings provide important insight into the mechanisms that may drive liver injury, and ultimately liver failure, in individuals with severe AH. Additional clinical and translational research is needed to more fully characterize the pathological mechanisms that contribute to severe AH and to identify novel therapeutic targets for this devastating disease.

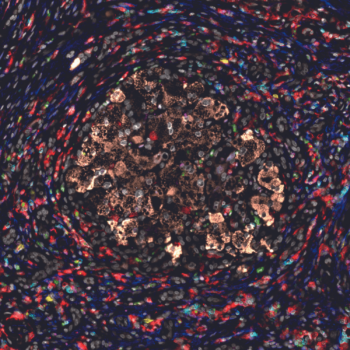

Image Caption: The image above shows staining of liver tissue from a patient with severe AH using different fluorescent colors to label different cell types. The staining reveals a broad array of inflammatory cells surrounding liver cells located in the center of the image.

Reference:

Ma J, Guillot A, Yang Z, Mackowiak B, Hwang S, Park O, Peiffer BJ, Ahmadi AR, Melo L, Kusumanchi P, Huda N, Saxena R, He Y, Guan Y, Feng D, Sancho-Bru P, Zang M, Cameron AM, Bataller R, Tacke F, Sun Z, Liangpunsakul S, Gao B. Distinct histopathological phenotypes of severe alcoholic hepatitis suggest different mechanisms driving liver injury and failure. J Clin Invest. 2022;132(14):e157780. PubMed PMID: 35838051

_____________________________________________________________________________

This article first appeared in NIAAA Spectrum.

To receive email alerts from NIAAA, sign up at https://public.govdelivery.com/accounts/USNIAAA/subscriber/new.